By Bea Bianca Nicerio, Terrence John Martin Fernandez and Claudette Marie Orosco

DARAGA, ALBAY— Amidst its dynamic daily market activity, the municipality of Daraga, Albay struggles with a severe waste management issue, confronting the pressure and choices in time, space, and possibilities for how this problem will be managed, improved, and minimized.

Aveian Argote, a resident suffering the “unbearable” smell coming from the local garbage disposal, the stink of poorly handled waste hangs thick in the air. She says, echoing a frequent complaint in her area, “The real problem for us is the very bad odor coming from the trash that gets tossed away.” Aside from the obvious suffering, Aviean’s worries are about the possible health risks. Given the daily battle with environmental health, “My main fear is the health risks we might face, as it doesn’t seem good and could possibly spread diseases,” she says.

She continued, “We’ve become somewhat accustomed to this smelly situation, although there are times when it doesn’t smell as bad. My hope for the future is that local authorities will relocate the garbage disposal to a better place, away from the residences.”

At the center of the town’s waste management effort sits at the Municipality Central Material Recovery Facility Materials Recovery Facility, a 3.2-hectare facility meant to process biodegradable waste into an organic fertilizer. But as the waste keeps piling, so do the problems.

Many problems arise from using a private sanitary landfill. Its private ownership limits the local government unit’s LGU garbage collection operations, as such restricting disposal hours and increasing the possibility of unplanned closures. Using this facility also adds to the expenses that really deplete the town’s budget.

Daraga also has a Municipality Central Material Recovery Facility Materials Recovery Facility (MRF), however, when the private landfill closes, this Municipality Central Material Recovery Facility Materials Recovery Facility (MRF), which was initially intended only for biodegradable waste, is forced to handle leftover waste as well. This results in a doubling of the garbage processed, which delays the entire system and increases costs and manpower.

Operating the Central MRF also presents challenges. Improper trash segregation at the source in the barangays causes residual garbage to mix with the biodegradable waste arriving at the MRF. Also, enhancing the MRF’s facilities and operations is difficult due to the municipality’s limited resources. Another issue that needs addressing is the odor from the rotting garbage, particularly because of its proximity to chicken farms.

The Department of Agriculture’s agricultural manager, Rabancos Edwin, explained, “We should only be receiving biodegradable waste, but due to the number of households and barangays that don’t comply, the waste we receive is still mixed, so the ending is that we still need to segregate properly at the facility.” He underlined that improper waste segregation is only the start of the issue.

Inside the MRF, what used to be an efficient vessel composting system has long been replaced by ground composting, an improvised method of sun-drying biodegradable waste due to the breakdown of equipment and lack of funds. Rebancos observes, “Before, the process was fast. Now, because there are no more funds for machine maintenance and the electricity is weak due to substandard wiring, we’re doing it manually.”

Iwa Besu, a privately owned landfill facility

Without its own transport vehicle, the MRF struggles to move residual waste to Iwa Besu Corporation, Daraga’s main sanitary landfill. “When the landfill closes, we are also forced to stock up on waste. It takes almost a month before it can be transported,” he added. The risks may be spoilage or leakage of residual waste, foul odors, and potential contamination out of this. “When the landfill closes, we are also forced to stock up on waste. It takes almost a month before it can be transported,” he added. The risks include spoilage or leakage of residual waste, foul odors, and potential contamination as a result of this.

Despite all these challenges, the MRF continues to produce about 600 kilograms of organic fertilizer daily, a silent victory amid an uphill battle in waste management.

Since 2017, Iwa Besu has provided a landfill for the wastes of Daraga as well as 36 other municipalities around Albay and Bicol Region. Located in Brgy. Mayon in Daraga, the landfill operates daily and every hour, receives multiple trucks from different LGUs containing waste for disposal. “We have provided the services needed by most LGUs since it’s hard to maintain a landfill,” said by Miguel Macandog, who operates the landfill.

It has acquired an Environmental Compliance Certificate (ECC) from the DENR and a Permit to Operate (PTO) from the Environmental Management Bureau (EMB), allowing them to operate the landfill and provide much-needed help to multiple LGUs while at the same time being friendly to the environment. “We ensure that the company complies with the DENR’s rules and regulations. By acquiring an ECC from DENR and getting a PTO. Also, by studying and improving our knowledge on waste management, from proper waste disposal to minimizing the environmental impacts of waste production.”

Iwa Besu’s impact has been felt within the municipality. “Daraga is the cleanest it’s ever been. No more problems with rubbish piling up on almost every post. Air pollution on the main streets in Daraga has vastly improved,” declared Macandog.

The Bigger System

Municipal Environment and Natural Resources Officer (MENRO) Officer Johnvic Grageda, said the MRF is supposed to handle only biodegradable and recyclable waste. But the reality is far more complicated.

“The majority of barangays are not complying with the regulations in terms of waste management. There are some stubborn ones who, even with instructions, still send residual waste,” Grageda said. He emphasized that many barangays do not comply with proper practice and he stressed the importance of the barangay’s role in segregation at the source. “If segregation is done properly at the barangay level, the load at the MRF will be significantly reduced”. He pointed out behavioral change is needed to improve waste disposal habits on each barangays and homes as he advocates community-based education programs and barangay enforcement.

Miguel Macandog, who operates the Iwa Besu Sanitary Landfill serving 36 LGUs in Albay, including areas beyond Daraga, explained, “When the main sanitary landfill is closed, the residuals are temporarily brought to the MRF—it’s just a temporary shelter. Only when it opens again do we then transport them.” He further stated, “Our role is just to provide and operate the landfill. Transportation falls under the LGU’s responsibility,” and added, “The real problem, and the solution, indeed starts at the household level.”

The present waste management of Barangay Market Site, Daraga, Bicol, as stated by Roberto Moral, emphasizes the community change, struggling with the fundamental yet vital element of garbage segregation. Though there is a mechanism for daily collection from Monday to Saturday and transport to a Material Recovery Facility MRF throughout its eight “puroks,” the biggest challenge is getting enough segregation at the source of the homes. Kagawad Moral claims this problem is not particular to Barangay Market Site but rather widespread throughout all–54 barangays in Daraga. Under the present emphasis, among the residents segregation policies are being implemented and enforced.

The San Ramon site receives the gathered trash from the Barangay Market Site, implying a consolidated disposal location for the city. Sometimes known as the Ecological Solid Waste Management Act of 2000, Republic Act 9003 directs their activities under an all-encompassing legal framework. Tracking compliance with this act, particularly with respect to segregation, though there is some community involvement, it appears to be based on information and education. Moral believes that educating people and underlining the importance of RA 9003 could help to create community participation. The enforcement aspect is also underlined; non-compliance alerts of penalties underlined this. The local government unit (LGU) plays a supportive role by issuing advice to the barangays, which are said to be followed.

“When the main sanitary landfill is closed, the residuals are temporarily brought to the MRF—it’s just a temporary shelter. Only when it opens again do we then transport them,” he explained.

Barangay-Level Reality

Kagawad Nixon Marqueses of Barangay San Ramon openly shared their limitations, stating, “We don’t have our own service for collection yet. We manage individually. Sometimes we use the ‘habal-habal’ motorcycle taxi of the village chief.”

Although he claimed their barangay complies with proper segregation, waste collection is inconsistent and reliant on manual labor. “We only transfer the waste to the MRF when the bins are full. I hope we can have our own truck,” he added.

This mirrors the struggles of other barangays. Even with RA 9003 (Ecological Solid Waste Management Act of 2000) in place, implementation suffers from budget constraints and poor coordination.

A Homegrown Solution

In the face of inconsistent waste collection, Alyssa Javier from Sagpon, Daraga, Albay—found a green solution rooted right at home. Inspired by her mother’s passion for gardening and plants, Alyssa and her family built their own compost pit to manage their biodegradable waste.

“The barangay no longer collects biodegradable waste, so my family decided to just create a compost pit,” she explained. “It helps a lot with my mom’s plants as it makes the soil healthier for our plants”. While non-biodegradable trash is still collected by an eco-aide, at a cost—their compost system turns kitchen scraps into nourishment for their home garden, proving that even small actions can cultivate big change.

Her story isn’t just one of frustrations but a model and alternative that people and barangays can acquire. By composting at the household level, Javier turns waste into fertilizer for their plants, reduces their trash output, and eliminates the health risks and contaminations of uncollected garbage.

Daraga’s waste management challenges are not isolated. They reflect a deeper issue that plagues many growing towns across the country: a lack of funding, fractured systems, and public apathy.

Rebancos emphasized, “When waste management is proper, food contamination can be avoided, and green life will be protected. For us, waste is not just waste—it’s wealth.”

The fight for a cleaner, greener Daraga needs more than just regulations—it requires education, funding, and above all, community responsibility. Whether it’s building a backyard compost pit or lobbying for better barangay support, the time to act is now.

After all, waste doesn’t manage itself.

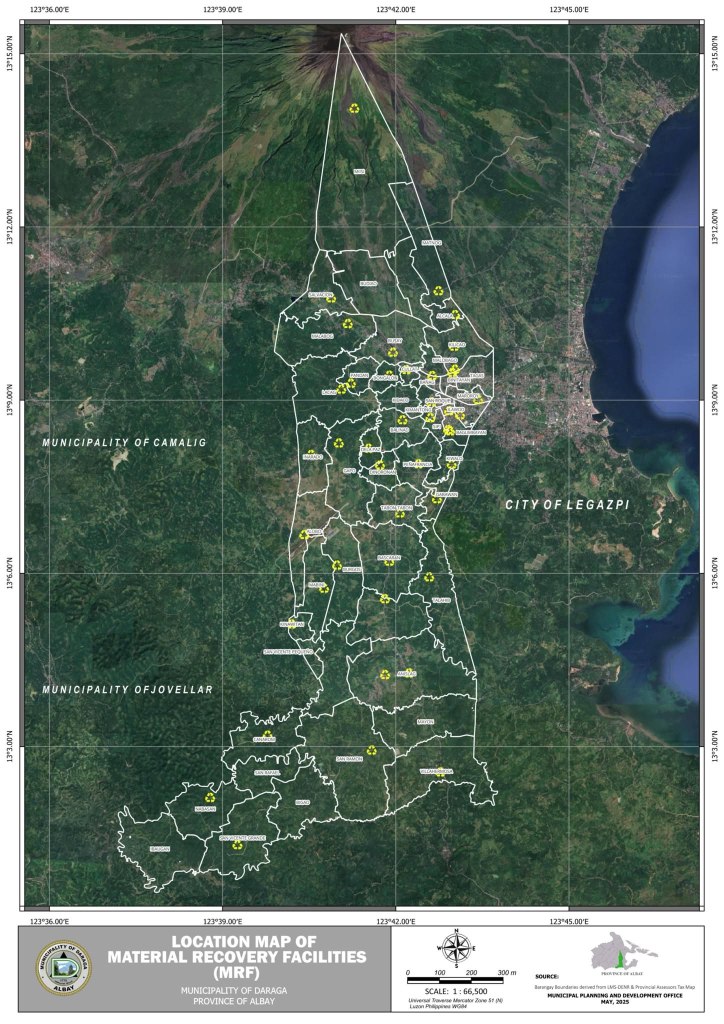

Location of every barangay MRF in Daraga

“In detail: Map of Daraga highlighting every barangay’s MRF’s location.”

Click to explore the different locations discussed in this story.

Leave a comment