by: Marl Kevin Calpe, Melrose Lagonoy, and Ayannah Raven Nuyles

The Bitter Bite of Bulok

In Ligao, where coconut palms shape both the landscape and the culture, there’s a good chance of you stumbling upon an unusual dish called Bulok. This traditional dish, which is made from the unopened coconut flowers, highlights the resourcefulness of the people, transforming what might often be overlooked and discarded into a nourishing staple. Passed down through generations, the people in Ligao believe that Bulok connects the community to their history.

But as environmental concerns loom over the Philippines’ coconut industry, can this dish survive without threatening the future of the very tree it comes from?

Sustainability

While Bulok has been a staple for generations, its impact on the broader coconut industry has raised questions. The Philippine Coconut Authority (PCA), an agency tasked with overseeing the coconut industry in the country, has expressed concerns about the practicality of using coconut flowers for food on a large scale. After all, the flowers play an essential role in the production of coconuts, which are a major agricultural commodity in the Philippines.

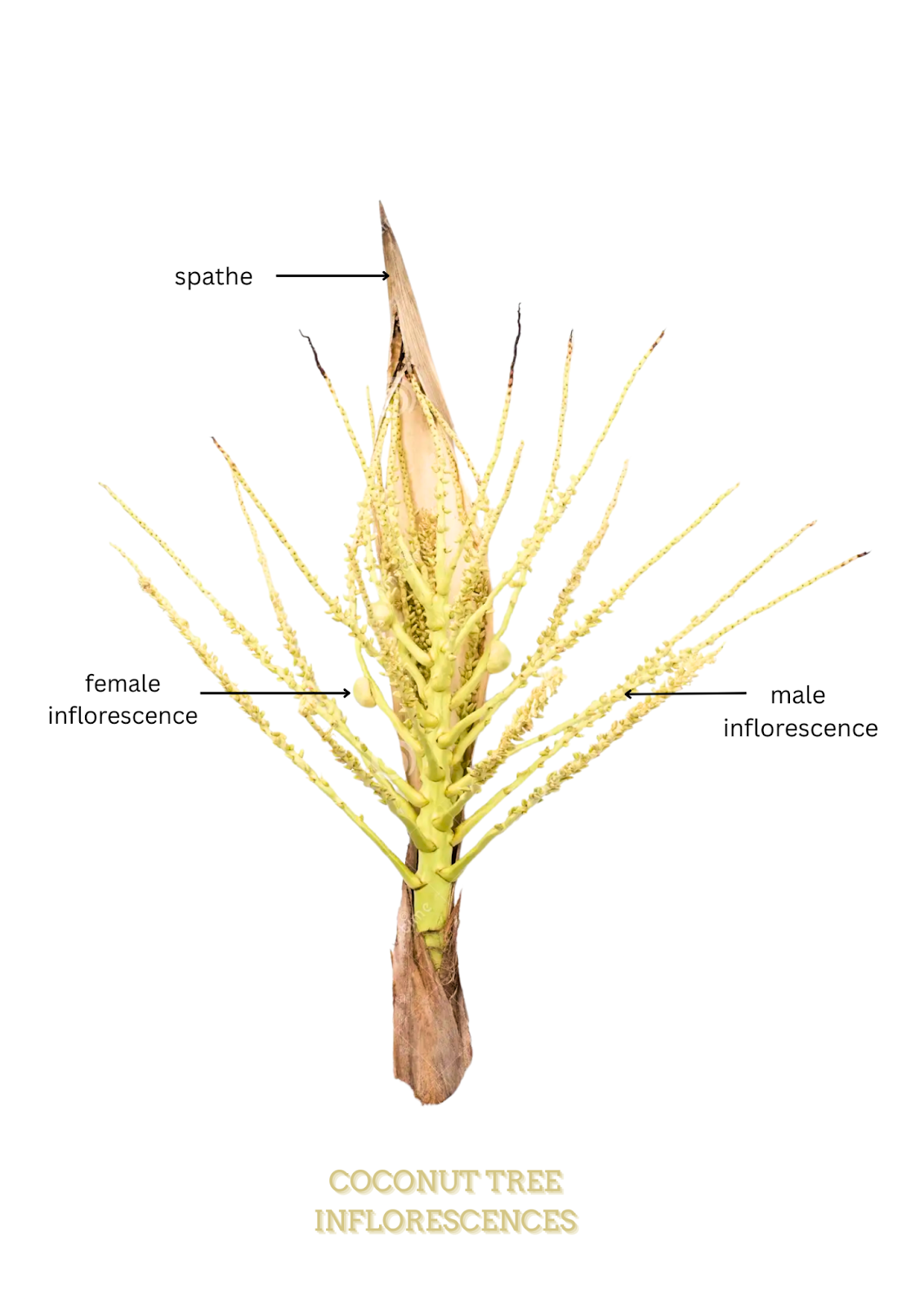

According to the PCA, each unopened spathe — the flower stalk — has the potential to produce five to six coconuts. These coconuts can later be processed into products such as cooking oil, copra (dried coconut meat), and coconut milk. Given that coconuts are a significant contributor to the Philippine economy, providing income to millions of farmers and workers, the decision to harvest the flowers for culinary use is a weighty one.

“Using the coconut inflorescence directly as food is uncommon,” the PCA notes in its statement. “It is impractical because the inflorescence bears the male and female flowers that later develop into mature coconut fruits.”

Ries Barcenas, a local chef, acknowledges this dilemma of balancing the harvesting of coconut flowers with the need to protect coconut fruit production. Bulok is an important dish, but it must be harvested with care.

Timing is critical — the flowers can only be harvested once the tree has begun to bear fruit. If harvested too early, the flowers will not develop into mature coconuts, and the tree’s overall yield will be affected.

“If you harvest the flower too early, it won’t turn into fruit,” Ries explains. “You can harvest once the tree already has fruits, but not if it’s just starting to flower.”

This delicate balance between tradition and sustainability is not lost on local farmers. The careful and selective practice of harvesting coconut flowers demonstrates a deep understanding of the environment and the needs of the coconut tree. Farmers have learned through experience when to harvest and when to leave the flowers be.

Biologist and educator Prof. Dean Carlo F. Galias believes that it is safe if the consumption remains local, “If you’re only after that [the dish], that’s it. You’re not killing the tree, actually it replenishes quickly,” he says.

“Besides, there are many coconut trees in the Philippines. They don’t flower one-time, big-time.” He notes that this is a situational scenario, and he suggests that the issue becomes critical only when it is commercialized beyond its home region.

“The moment Bulok is marketed largely outside the city, only then should it be a cause for concern as it could potentially mark the start of its decline.” he added.

However, concerns remain about the long-term impact of harvesting the flowers, especially as the country faces challenges related to coconut production.

In its reports, the PCA also highlights the economic risks of such practices. While small-scale harvesting may have minimal immediate effects on coconut yields, the practice could become unsustainable if adopted on a larger scale or if done improperly. The PCA stresses that the coconut industry’s future depends on ensuring that these trees continue to produce fruit, and any significant disruption in coconut production could have severe repercussions for both local economies and the national market.

Ma. Teresa I. Namia, Acting Department Manager II of Albay Research Center of PCA, warns that large-scale or poorly timed harvesting of coconut flowers could disrupt the production of coconuts, leading to far-reaching consequences for local ecosystems. Coconut trees support local biodiversity, and any reduction in fruit yield could have ripple effects, affecting not just the livelihoods of farmers but the wildlife that depends on these trees.

“Large-scale or poorly timed harvesting could disrupt coconut fruit production and affect broader ecosystem services.”

Ma. Teresa I. Namia

Traditional Cooking

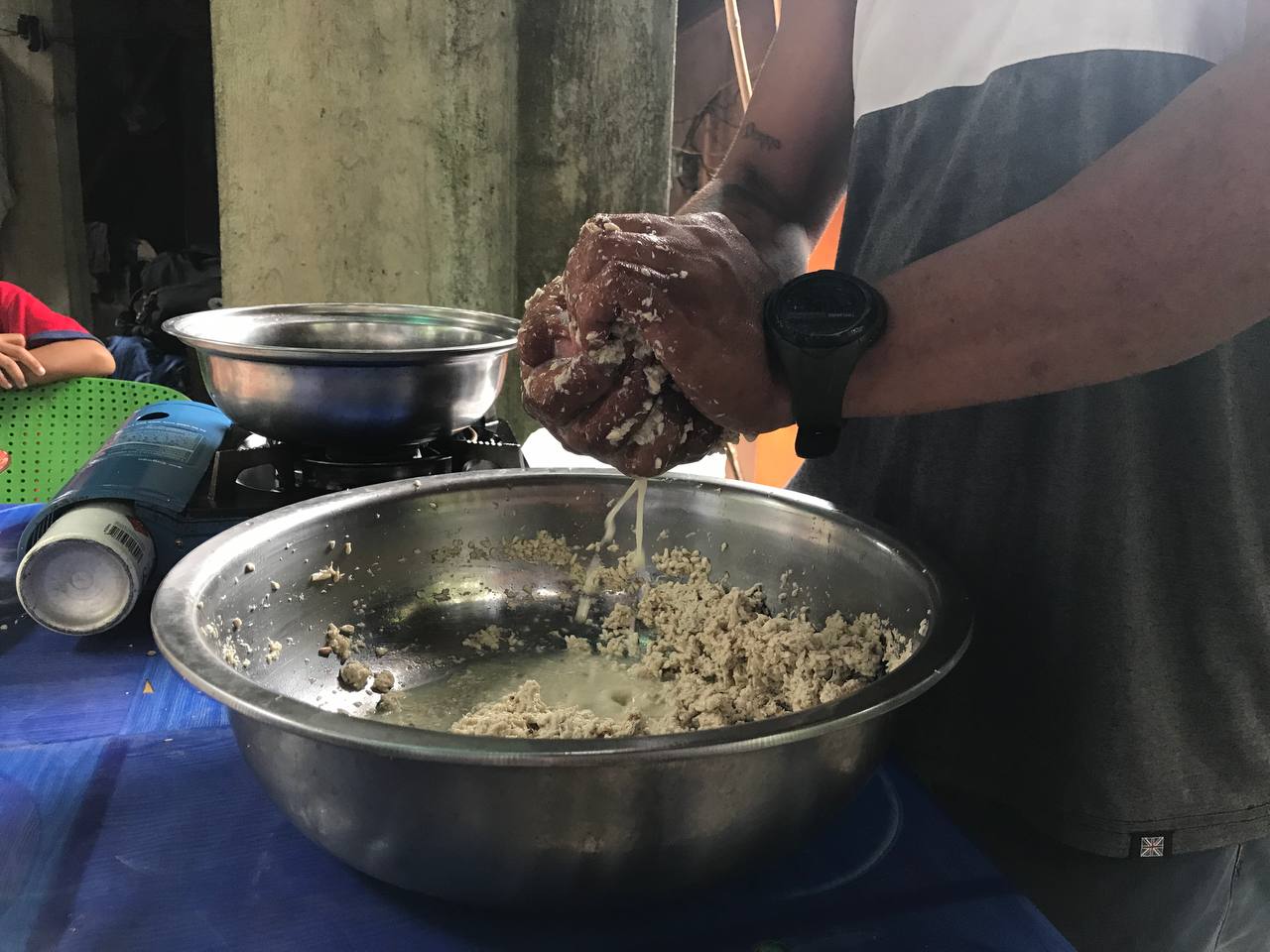

Ries, cooks Bulok with the same care and regard he would for any treasured family recipe, in the dimly lit side of his kitchen, with pots and pans hanging from the walls along with the gentle hum of a fan moving the warm air. His kitchen is scented with garlic, onions, ginger, and the smoky aroma of tinapa (smoked fish). The coconut blooms, which are still enclosed in their spathe, are the center of attention. These flowers, with their delicate yet sturdy nature, become the base of Bulok.

At 15, Ries already knew how to prepare and cook Bulok after learning from his chef neighbors. “I started helping in kitchens when I was just nine years old. Since then, I learned how to make Bulok just by watching the chefs,” Ries says, as he carefully slices through the flowers. “At first, I only washed dishes during weddings. After about five years, I became an assistant chef, and eventually, the chef.”

In the same way that coconut palms draw life from their roots, Ries also believes that Bulok is a deep connection to his roots. A dish passed down from his father through his ancestors—a link to the past, and one that has persisted through generations.

“When I was young, Bulok was served during weddings, fiestas, and any occasion where food was plentiful and shared,” Ries explains as he stirs the dish, the coconut flowers absorbing the flavors of the tinapa and the ginger. “It’s a refreshing dish that lightens the meal, especially when it’s heavy with meat.”

On top of that, Bulok is both rare and fleeting— it is a food borne out of an understanding of nature’s cycles, of knowing when to harvest, and how to transform what is otherwise discarded into something precious. There is no room for delay, no opportunity to store them. They must be enjoyed in their moment of peak freshness, making Bulok a delicacy that is tied to the rhythms of nature.

“It’s difficult and laborious, You have to cook them right away. If you pick them today, you must cook them today; otherwise, they spoil.”

This urgency is what gives Bulok its unique flavor and texture — it is a dish that cannot be mass-produced or commodified in the way that many other foods can.

The fleeting nature of the coconut flower, combined with the precise timing required for harvesting and cooking, has kept Bulok from becoming a widespread dish. It remains a regional specialty, largely confined to the areas of Ligao and other parts of the Bicol Region. For many, this is part of its charm — a hidden treasure, something that is uniquely Ligao. But for others, it is a symbol of how fragile and fleeting tradition can be. As the world changes, as the forces of modernization and industrialization reshape the landscape, the survival of traditions like Bulok becomes uncertain.

Decline

Compounding these challenges is the reality that coconut production in the Philippines is declining. The country’s coconut trees are aging, and many are over 60 years old. Without widespread replanting, coconut yields are decreasing, and farmers are struggling to keep up with the demand. Typhoons, pests, and diseases like Cadang-cadang, which have killed millions of coconut trees, only add to the uncertainty. In the Bicol Region, where coconuts are integral to both the local economy and culture, the future of the coconut industry is in jeopardy.

The Philippine Statistics Authority shows a slight decrease in coconut production, with the volume dropping to 14.89 million metric tons (MT) in 2023 from 14.93 million MT in the previous year.

Centralizing on this issue, PCA aims to replant around 8.5 million trees in 2025, with expectations to ramp up annual planting in the succeeding years, to plant 100 million coconut trees by 2028. The initiative not only seeks to restore declining yields but also aims to secure the livelihoods of millions of coconut farmers and protect cultural food traditions.

When coconut trees fail to bear fruit, families lose income, and the traditions that rely on the tree’s bounty — like Bulok — begin to fade. What was once a food source born of necessity has now become a rare delicacy, endangered not just by the fragility of the tree, but by the challenges of modern agriculture.

Yet in the face of these challenges, Bulok remains a symbol of resilience. During lean seasons, when rice is scarce and vegetables hard to come by, Bulok becomes a crucial source of sustenance. It is a reminder of how the land, even in its most vulnerable state, can provide.

“Bulok has helped us get by,” Ries reflects. “It fills you up. It’s food from the tree, without waiting for fruit.”

The irony is palpable: a dish born from ingenuity and survival during hard times now faces extinction due to the very fragility of the tree it depends on.

The future of Bulok hinges on the choices made today. The Philippine Coconut Authority has acknowledged the dish’s cultural value, but it also cautions that the economic risks of harvesting coconut flowers must be carefully considered. As the coconut industry grapples with decline, Bulok remains a culinary casualty of a changing world.

In Ligao, the fragrance of Bulok still fills the air during special occasions. But whether this dish will survive into the future, whether it will be passed down to future generations, or whether it will fade into history, is uncertain. The future of Bulok is intertwined with the fate of the coconut tree — and with it, the cultural identity of Ligao.

As the community faces these challenges, a larger question remains: Can tradition coexist with sustainability? The future of Bulok will depend on the delicate balance between preserving the past and adapting to the needs of the future. Only by honoring both the heritage of the coconut tree and the importance of environmental stewardship can Bulok survive, as a living testament to the resilience of both people and land.

Would you try Bulok if it meant harming future coconut yields?

Leave a comment